Why Journalism Matters

Courageous female journalists fighting the long game for justice in Colombia and Japan. The Scam Empire costing a fortune and creating misery around the world

4 minute read

A Colombian investigative journalist’s long wait to tell the truth

Everyone knows that investigative journalism often requires courage and tenacity but patience is not often given the prominence that it deserves—especially if that patience stretches over decades.

In countries recovering from decades of conflict like South Africa, and more recently Colombia in South America, journalists have sometimes had to show incredible patience in the wait to showcase traumatic truths.

But this does mean that after many years the story can be told more completely, more effectively and more securely than an attempt to capture an early scoop or exclusive.

This has been a lesson hard earned by Colombian Investigative reporter Ginna Morelo who has spent more than a decade investigating the crimes committed by right-wing death squads at the University of Córdoba

Morelo is well recognised for her work in Colombia. She is a five-time winner of Colombia’s highest journalism award, the Premio Nacional de Periodismo Simón Bolívar, and has received international prizes, including from the Sociedad Interamericana de Prensa and the Premio Ortega y Gasset.

She has covered many aspects of the civil violence that wracked Colombia from the 1960s until 2016, believed to have been the longest armed conflict in the Western hemisphere.

Security Forces

The war involved fighting between the government security forces and left-wing guerrilla groups but gradually encompassed far-right armed groups who often acted in co-ordination with state security agents

Although Morelo reported on many aspects of the conflict she reluctantly decided that one particular situation was too dangerous and sensitive to write about. That involved the violence carried out against staff and students at the University of Córdoba by right wing paramilitaries who operated under the name of United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia known by the acronym AUC.

The story Of Morelo’s involvement with the university’s take over by the AUC is told in a report for the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) by Miriam Forero Ariza a Colombian journalist and data journalism expert.

Ariza writes: “Members of the AUC later acknowledged as part of a demobilization process that they murdered professors, students, and labour unionists with a leftist ideology across the country. But back then, this ideological takeover — backed by force — was a secret, and many of Morelo’s sources were paralyzed with fear.”

Morelo discovered that this takeover was part of an organised campaign by the AUC to eliminate any trace of ‘leftist’ ideas.

“Armed groups controlled the appointment of the university rector, banned library books, and exacted physical punishments, she found. The takeover resulted in dozens of people being killed or disappeared, pushed some intellectuals into exile, and forced the interruption of academic projects on topics such as food security and climate change. It also led to a local population plunged into fear and silence.”

A threat

Part of that story, as a result of Morelo’s initial reporting, was due to appear as a chapter in her 2009 book “Tierra de Sangre, Memoria de las Víctimas” (Land of Blood, Memory of the Victims) — which was based on survivors’ accounts of the conflict in Córdoba. Just as she was about to go to press, however, Morelo received a phone call that shook her: a threat against her two children. She called the publisher and told them to halt publication.

During the past four decades, 2,546 reporters in Colombia have been threatened due to their work, according to the Colombian Press Freedom Foundation.

It would take more than a decade for her to feel that the security situation was sufficiently changed for her to publish — and 13 years after her first book about the paramilitary influence in Córdoba, she released “La Voz de Los Lápices” (The Voice of the Pencils), in 2022.

To decide if it was finally safe, Morelo used a risk assessment method, with the help of a colleague, a social scientist, and her own sources — the survivors of the violence — who finally told her: “It’s time. We are ready.”

Morelo says that it’s important for reporters in a similar position to consider a golden rule: the importance of protecting the lives of reporters, sources, and those around them. As Morelo puts it: “We have no right… to put at risk the lives of the people who love us.”

After years of trying to tell the story, she found survivors who were finally willing to talk to her. Many had written down their memories, keeping a note of the events at the campus during the takeover, with records added in the intervening years.

“As journalists, we are not the owners of any story. Not even if we have the byline. Stories are created over time in people’s memories,” says Morelo.

“When a journalist is told that it’s not the right time and that they can’t publish yet, they say: ‘This is the end.’ But for me it wasn’t the end. For me it was like the best invitation I’ve ever received because from the moment I slowed down, I was able to look back at that memory of the past and see what was happening, the real background of the countercultural project [at the University of Córdoba],” Morelo explains. “So, it’s not the final product that makes me happy, but the process and the lessons learned.”

Reference

3 minute read

A remarkable Japanese documentary about a journalist who tells her own story of surviving sexual assault

The Black Box Diaries is a remarkable documentary about a female Japanese journalist investigating a sexual assault against her.

Ito also directed the film which was based on her memoir Black Box. Even though the film was nominated for an Academy Award in the US this year it has yet to be shown in Japan. In the opening scene journalist Shiori Ito explains in a video diary clip: “I have a chance to talk about the truth… which has been ignored.”

Her story is outlined in a report for the Global Investigative Journalism Network by Ngozi Monica Cole a writer and journalist from Sierra Leone .

As Cole reports: “In April 2015, Ito, then a 25-year-old intern at Thomson Reuters, met Noriyuki Yamaguchi, the Washington DC bureau chief of the Tokyo Broadcasting System for dinner to discuss a possible job opportunity.

“In the documentary, Ito recounts how she can’t remember anything from that night after suddenly getting ill during the meal. She only remembers waking up in a hotel room hours later to Yamaguchi sexually assaulting her. Two years later, Ito went public about the assault and was met with vilification and backlash. At the time, only a few colleagues showed support and only one media outlet covered the story.”

Ito spent the next five years piecing together what happened to her through video diaries, CCTV footage, and phone recordings.

“In this story I was a journalist and a survivor. And because of that, I questioned myself many times whether it was okay to look into my own case.”

Cole’s report continues: “In 2019, Ito won a lawsuit against Yamaguchi, which found him liable for sexual assault despite his denials. The court also dismissed a counter-suit by him claiming defamation by Ito. Three years later, Japan’s Supreme Court upheld a high court decision that there had been sexual intercourse without consent and directed Yamaguchi to pay her more than US$30,000 in damages.

“The film, which has not yet been shown in Japan, has resonated with audiences all over the world. In the lead-up to the 69th Session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women, the film’s producers, Think-Film Impact Production, partnered with the Japan Society to host a reception in New York City, bringing together policymakers, journalists, and experts to discuss the film’s call to action in holding perpetrators accountable and supporting survivors of sexual violence.

“We’re hoping that in the US, the film will help hold accountable corruption and abuse of power that is happening in many facets of society,” says Meredith Goldberg-Morse from MTV Documentary Films, the documentary’s US distributor. “It’s also about empowering the next generation of women in journalism so that these stories continue to be told.”

According to research only 4% of sexual assault cases in Japan are reported to authorities and Ito’s story is an indication of why that is the case.

Ito had to go through a humiliating reporting process including reenacting her rape with a life-size doll in front of police officers. As a result she decided not to pursue charges.

“Ito also acknowledges the extreme vulnerability of laying her trauma bare and not being a neutral, third party to the story. There are several scenes where she shows that vulnerability, including moments where she is reading hate mail as well as having derogatory names yelled at her outside the court.”

The eight gruelling years she put into the making of Black Box Diaries has made Ito uncertain about returning to a career in journalism, but she recognises the importance of telling a personal story.

“I’ve been talking to my journalist friends, and we kind of started saying that we do need more personal perspective journalism. Especially in today’s world, we need more of a personal perspective investigative story, because otherwise who would do it? Who else can do it?”

The experience has also made Ito appreciate the importance of collaboration.

Facing indifference in Japan, she says “international support was the lifeline for this documentary…always find possible international collaborators when topics are hard to talk about in your country.”

Reference

5 minute read

How the Scam Empire reaches out across the world—with only investigative journalists in pursuit

A major journalistic investigation unveiled this month reveals the frightening scope and damaging impact of cyberfraud networks on ordinary people around the globe.

Co-ordinated by the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) Scam Empire is a collaborative investigation involving Swedish Television (SVT), and 30 other media partners from many countries.

The investigation is based on 1.9 terabytes of leaked data and involves the operation of two groups of highly organised and sophisticated call centres based in Israel, Eastern Europe, and Tiblisi, the capital of Georgia, selling phoney ‘investments’ to at least 32,000 people totalling at least $US275 million.

Police authorities estimate the costs of the cyberfraud industry in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Jürgen Stock, the former secretary general of Interpol, said online scams generate about $500 billion per year.

The leaked data includes over 20,000 hours of phone calls and tens of thousands of screen recordings. They show that when ‘investors’ try to withdraw their ‘profits’ scammers invent reasons why money can’t be sent and trick these clients into sending more.

AS OCCRP reports: “Though the scammers’ methods are crude, their work is highly organised, operating out of city offices on a commercial scale. They use client management software, collaborate with external marketers, and provide days-long trainings for ‘client’-facing staff — who are backstopped by human resources, quality control, and IT departments.

Extremely lucrative

“These schemes are extremely lucrative. The scammers — whose efforts are tracked on leaderboards and who celebrate their wins with animated gifs — are rewarded with lavish parties, generous salaries, and performance bonuses.”

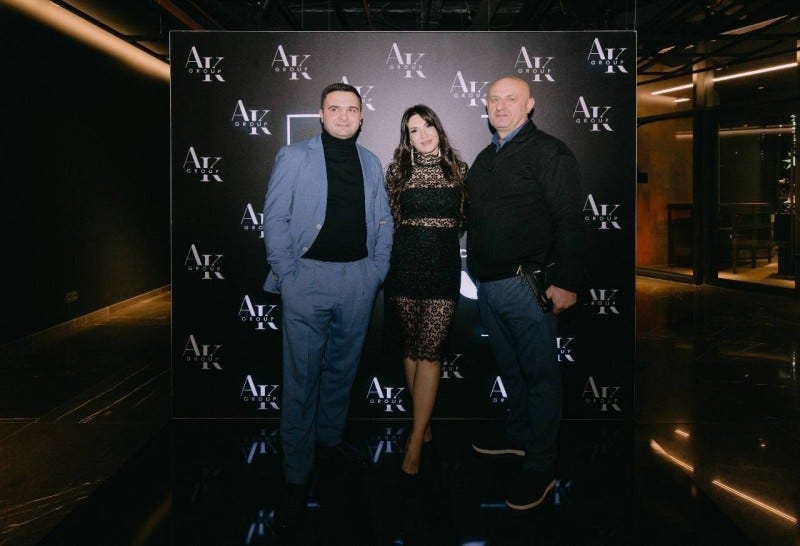

It was discovered that “A.K. Group” had at least three offices in Tbilisi, and employed around 85 people, including back-office staff, as of April 2024.

“The other operation[based in Israel and Europe] is much larger and more diffuse. It is divided into three broad business units with their own management structures, and has had at least seven offices in Israel, Bulgaria, Ukraine, Spain, and Cyprus that employed several hundred people as of August 2023.

“These divisions recorded payments from ‘investors’ centrally and appear to be working under the direction of a management team in the Tel Aviv metropolitan area. The leaked data does not reveal whether one or multiple people are behind this operation.

The leak came from an anonymous source to Swedish Television and, unusually, the whistleblowers issued a statement explaining their motivation, revealing how, in the face of inertia and inactivity on the behalf of police and government authorities, investigative journalism held out the most hope of ending impunity for the scanners.·

Operate openly

The source wrote: “Fraudsters can operate almost openly, without anyone stopping them. Almost none of these crimes ever get resolved because of the difficulties in investigating crimes across borders. … Without real international change, this will never go away.”

“By turning over the material to the media, I/we hope this issue gets enough attention for authorities to take action against these criminals. This problem is not impossible to solve. We all just need to care enough to do something about it.”

The international reporting team were able to reach many of the victims and confirm the scale of the losses sustained.

As OCCRP reports: “The statistics speak for themselves: Reporters reached 182 people who were listed in the data as having ‘invested’ money. More than 90 percent of them, or 166 people, said they had been the victims of a scam. Their total confirmed losses exceeded $21 million, and 85 of them told journalists that they had gone to the police.”

“… the operations appeared to close when reporters reached out to them. Their employees avoided speaking and were protected by security guards. In Georgia and Bulgaria, entire offices appeared to empty after reporters made contact.”

By looking for clues in chat conversations and cross-checking them through social media posts and other publicly available information.reporters were able to identify many of the scammers.

They discovered through A.K. Group files that the company is owned by a 36-year-old woman named Meri Shotadze. However other internal communications show, she appears to be second-in-command. The man she refers to as her boss is a 33-year-old man named Akaki Kevkhishvili. who appears to enjoy such luxuries a US$100,000 Range Rover, but there may be others behind these two. Neither Shotadze nor Kevkhishvili responded to requests for comment.

· “Despite law enforcement efforts, these scams continue to evolve. The industry thrives because of its ability to cross borders with little effort — scammers can quickly switch servers, move money through a web of international transactions, and target victims in far-away countries.

· “Platforms like Google and Facebook have also played an unwitting role in the industry’s success, profiting from ads that funnel victims into these schemes. With enforcement fragmented across jurisdictions, the battle against online investment fraud remains an uphill struggle: For every network that gets dismantled, another seems to emerge.”

Professionally structured

“These call centres are extremely professionally structured and organised and are managed accordingly,” said Nino Goldbeck, a senior public prosecutor in the German state of Bavaria who specializes in cybercrime.

“Well equipped, good IT, good equipment…We’ve often been really amazed at how well they work, how well everything is monitored and recorded. In our opinion, the accounting in such companies is sometimes almost better than in many completely legal companies.”

But the slick operations mask a trail of misery for ordinary people around the world.

Many victims are left penniless and on the verge of suicide but the scammers— who adopt false identifies and use software that can create illusory ‘profits— continue to plague their clients, sometimes posing as government officials who can help victims recover their losses—by paying an additional fee.

So far no one has been prosecuted as a result of the Scam Empire leak, but thanks to investigative journalism at least suspects have been named and the situation is out in the open.

Reference

OCCRP Scam Empire Investigation

It’s free to subscribe and you can cancel anytime, so give it a try!

Contact us on greatjournalismwjm@gmail.com

Follow us on Facebook and Twitter

facebook.com/whyjournalism matters

X-twitter @JournalismWhy